The exact time of the creation of Georgian script is not fully determined in science, but we can trace the development of calligraphy at least from the 5th century. The first samples are executed in Asomtavruli letters with strictly observed geometric principles. These include lapidary (carved on stone) and mosaic inscriptions from Palestine, inscriptions of Bolnisi Sioni and Jvari Monastery in Mtskheta, and others. The oldest Georgian calligraphic samples (5th-7th centuries) using ink and pen have survived in the form of palimpsests: the ink was washed off from old manuscript pages and new texts were written over them. Fortunately, the lower layer is still legible, albeit with difficulty. It is thanks to this that we know how the first Georgian calligraphers wrote.

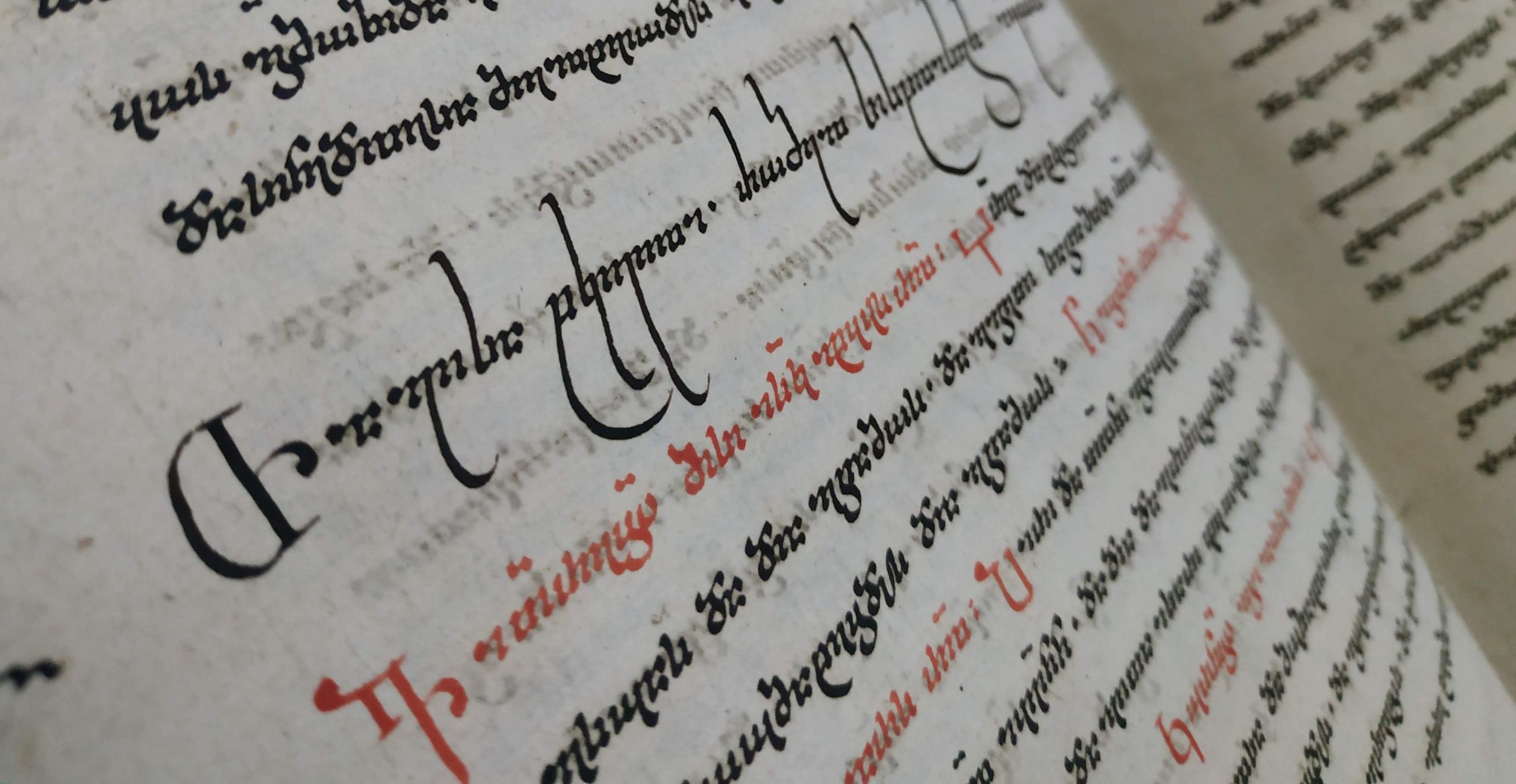

As years pass, the strict geometric structure of Georgian letters, established rules and standards are sometimes intentionally, sometimes unintentionally violated. The number of literate people increases. Some write beautifully, others not so much. The boldest calligraphers begin to explore and, inspired by "distorted" forms, create new, most beautiful outlines. This is how a new Georgian script - Nuskhuri - emerges. In the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries, numerous calligraphic schools are formed in monastic scriptoriums: in Palestine, Egypt, Syria, Greece, Bulgaria, Tao-Klarjeti, and various regions of Georgia. It can be said that Georgian calligraphic creativity of this period has no boundaries, both literally and figuratively.

In addition to meticulously copied spiritual manuscripts and stone-carved inscriptions, royal documents were also written in a quick and businesslike hand. However, businesslike doesn't mean unattractive! Moreover, one of the proofs of the cultural or political strength of the kingdom was the visual aspect of the documents, including refined calligraphy. Therefore, for royal documents, calligraphers specially develop a handwriting that is both beautiful and quick to write. This is how the third Georgian script - Mkhedruli - is created and developed, with the first samples dating back to the 10th century.

Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, and Mkhedruli scripts were used and developed in parallel for centuries. Georgian calligraphers never stopped searching for new outlines. That's why all three Georgian scripts have numerous subtypes and calligraphic variations: Asomtavruli differs for books, titles, inscriptions, frescoes... Sinai-Palestinian and Tao-Klarjeti Nuskhuri are different from each other... Mkhedruli from the times of David the Builder and Queen Tamar might be very difficult to read for today's readers... Great calligraphic diversity, constant search for innovation while maintaining the old, is the most traditional characteristic of Georgian calligraphy.

This tradition is interrupted at the beginning of the 20th century. This era, full of paradoxes, extended its ideology to Georgian calligraphy as well: "The past is bad, everything new should serve new ideas." This approach led Georgian calligraphy down a strange, previously unknown path, towards which we may have very ambivalent attitudes: on the one hand, the centuries-old tradition of Georgian calligraphic art was completely rejected, knowledge and experience were lost, which in itself continues to have a negative impact on contemporary art... On the other hand, Georgian calligraphers were forced to create something that would not remind us of the past at all: they stepped into a completely new, unexplored field and found outlines that were previously completely unimaginable for Georgian calligraphic art. The boundary between "Georgian" and "non-Georgian" lines was blurred. Therefore, despite the fact that sometimes these explorations served very radical and unacceptable ideologies from today's perspective, the result is still interesting for modern Georgian calligraphers.

From the second half of the 20th century, especially towards its end, Georgian calligraphy gradually begins to restore connections with past traditions. Book, poster, and inscription designers emerge who specifically use old-fashioned letter connections, allusions, and echoes of Nuskhuri and Asomtavruli. New handwritten books are even created, serving to restore the centuries-old tradition. Competitions are held, as a result of which calligraphy gains more and more popularity among young people.

Finally, the Georgian Calligraphers Association is established, whose goal is inspired by the idea of Georgian calligraphers from many centuries ago: maintaining, respecting, vitalizing, developing the old tradition, and at the same time, constantly striving for new forms, new outlines, and ideas.